History and Tradition

Pico Island lace has deep roots in local history and culture. This craft tradition has not only played a fundamental role in the lives of the island’s women, but has also been an important source of income for many families over the centuries. The art of lace making, with its detailed and delicate techniques, has been passed down from generation to generation, perpetuating itself to this day and preserving a cultural legacy that continues to be a source of pride for the community.

Lace History

Lace production in Pico dates back several generations, and its origins have been directly linked to the need for women to find ways of making an economic contribution to their families. Initially, handmade lace production was an exclusively domestic activity, carried out in the family environment, where women passed on their knowledge to their daughters and granddaughters. This tradition was formalized during the 19th century, when Azorean immigration to the United States brought back more refined lace making techniques, adapted to local conditions.

During the 20th century, the practice of lace making was essential to the local economy. The lace makers began to collaborate with traders, who promoted lace exports to international markets. The ability to create delicate and unique pieces, often decorated with floral and geometric patterns, became a distinctive feature of Pico’s lace makers.

Durante o século XX, a prática das rendas foi essencial para a economia local. As rendeiras começaram a colaborar com comerciantes, que promoviam a exportação das rendas para mercados internacionais. A habilidade de criar peças delicadas e únicas, frequentemente decoradas com motivos florais e geométricos, tornou-se uma característica distintiva das rendeiras do Pico.

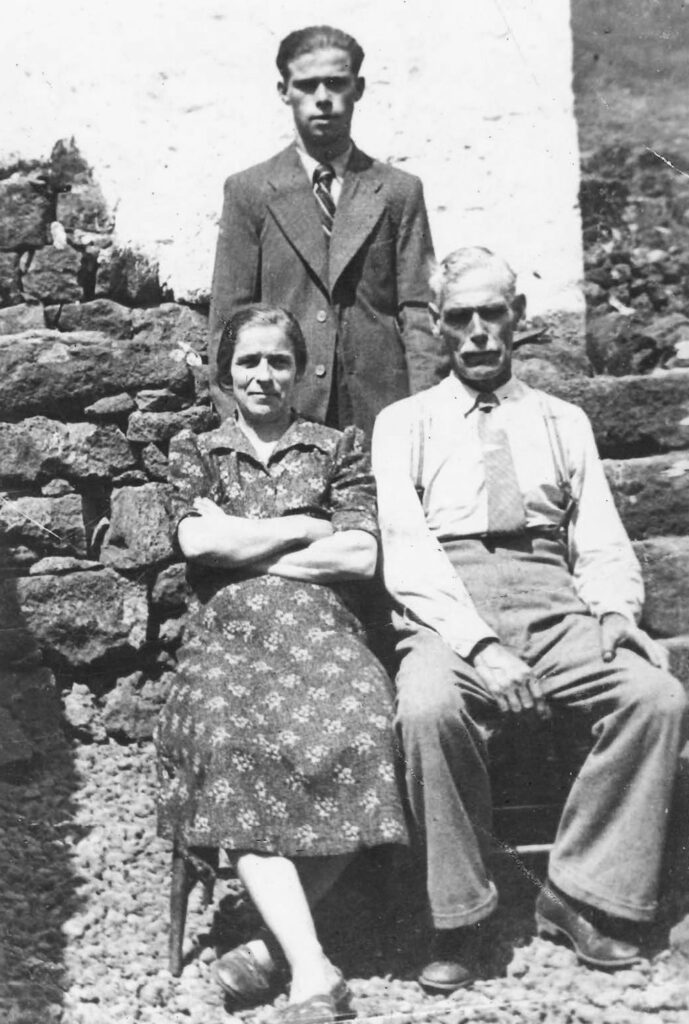

PICO ISLAND’S FIRST BUSINESSWOMAN

ROSA GARCIA

At the age of 20, she was the first businesswoman on Pico Island, selling lace.

At the time, she was advised to sign up as an entrepreneur at the Horta Chamber of Commerce and Industry, due to her high number of sales.

Rosa Garcia is a symbol of female empowerment on Pico Island, through the commercialisation of lacework and her dedicated efforts in education, particularly, and in driving the economic growth of many families on the island.

The First Female Job in the Azores

(Master Weavers)

In the 17th century, weaving was recognized as the first female job in the Azores.

Women who practiced this art were known as “master weavers” and played a central role in the production of textiles, using locally grown linen. This formal recognition gave women a prominent position in the rural economy, and weaving became one of the most respected jobs. The control of this activity was in the hands of the town councils, which regulated and authorized the weavers’ practices.

This activity was vital for the production of clothing and other fabric items, and it was from this practice that the lace tradition developed. The “masters” were responsible for teaching the weaving and lace techniques to the younger generations, keeping the tradition alive. The work of the master weavers laid the foundations for the inclusion of women in the craft labor market, a reality that would be consolidated in the following centuries with the development of other forms of handicraft.

Este trabalho era vital para a produção de vestuário e outros artigos de tecido, e foi a partir desta prática que a tradição das rendas se desenvolveu. As “mestras” eram responsáveis por ensinar as técnicas de tecelagem e renda às gerações mais jovens, mantendo viva a tradição. O trabalho das mestras tecedeiras lançou as bases para a inserção das mulheres no mercado de trabalho artesanal, uma realidade que se consolidaria nos séculos seguintes com o desenvolvimento de outras formas de artesanato.

| Lace Maker’s Name | Location | Specialty | Genaration | Reference Decade | Main Tecnique | Famous Products |

| Rosa Garcia (Rosa da Ponte) | São Mateus | Comercialização | 1ª | 1890-1920 | Farpa | Organizou produção |

| Maria Adelaide | Calheta de Nesquim | Tecelagem | 1ª | 1880-1910 | Tecelagem | Mantas e Meias |

| Goretti da Maria do Bezerra | Calheta de Nesquim | Renda de Gancho | 2ª | 1940-1970 | Farpa | Peças decorativas |

| Cecília Dias de Melo | Calheta de Nesquim | Renda de Gancho | 2ª | 1890-1920 | Farpa | Primeira geração de rendas de gancho |

| Jesuína Margarida Garcia de Lemos | São Mateus | Renda de Gancho | 2ª | 1900-1930 | Farpa | Colchas e peças decorativas |

| Maria Zulmira Raimundo de Lemos | São João | Renda de Gancho | 2ª | 1900-1930 | Farpa | Colchas e toalhas |

| Maria Adelaide da Silva | São Mateus | Renda de Farpa | 2ª | 1900-1930 | Farpa | Toalhas e peças pequenas |

| Clara Lemos Faria | São João | Renda de Farpa | 2ª | 1900-1930 | Farpa | Toalhas e colchas |

| Teresa Perdigão | Lajes do Pico | Renda de Agulha | 2ª | 1910-1940 | Agulha | Panos de mesa |

| Maria Lucília | São Mateus | Croché de Farpa | 3ª | 1940-1970 | Farpa | Colchas, Toalhas |

| Norberta Amorim | Piedade | Renda de Bilros | 3ª | 1940-1970 | Bilros | Toalhas de mesa |

| Silvina Garcia | Madalena | Renda de Gancho | 3ª | 1940-1970 | Gancho | Toalhas e Naperons |

| Fátima Azevedo | São Caetano | Renda de Gancho | 3ª | 1940-1970 | Farpa | Tapetes |

| Maria Conceição Goulart | São Caetano | Renda de Gancho | 3ª | 1940-1970 | Farpa | Tapetes |

| Alice Costa Machado | São Mateus | Renda de Gancho | 3ª | 1940-1970 | Gancho | Tapetes e Amorinhas |

| Liduína da Glória Ávila | São Mateus | Renda de Farpa | 3ª | 1940-1970 | Farpa | Colchas e toalhas |

| Teresa Margarida | São Mateus | Renda de Farpa | 3ª | 1940-1970 | Farpa | Toalhas e colchas |

| Maria de Jesus Matos | São Mateus | Renda de Farpa | 3ª | 1940-1970 | Farpa | Colchas e Tapetes |

| Noélia | São Mateus | Renda de Gancho | 3ª | 1940-1970 | Gancho | Amorinhas e Margaridas |

| Maria da Olívia | São Caetano | … | … | … | … | … |

| Maria do Ernesto | Candelária | … | … | … | … | … |

| Mariazinha do Franklim | Candelária | … | … | … | … | … |

| Maria Isilda | Candelária | … | … | … | … | … |

| Maria Isilda do Ernesto | Candelária | … | … | … | … | … |

| Mãe da Judite | Candelária | … | … | … | … | … |

| Esposa do João Lino | Candelária | … | … | … | … | … |

| Telma | Candelária | … | … | … | … | … |

| Filhas da Francisca Ferreira | Mirateca | … | … | … | … | … |

| Maria do Gonçalves | São Mateus | … | … | … | … | … |

| Adelina | São Mateus | … | … | … | … | … |

| Maria Palmira | São Mateus | … | … | … | … | … |

| As “Mudas” | São Mateus | … | … | … | … | … |

| Hélia | São Mateus | … | … | … | … | … |

| Telma | São Mateus | … | … | … | … | … |

| Hélia | São Mateus | … | … | … | … | … |

| Regina | São Mateus | … | … | … | … | … |

| Hortência | São Mateus | … | … | … | … | … |

| Maria Leonor | São Mateus | … | … | … | … | … |

The Influence of Convents on Embroidery (17th and 18th Centuries)

Female convents played a crucial role in the preservation and dissemination of crafts, including embroidery and lace, between the 17th and 18th centuries. In the Azores, convents such as Glória, in Angra do Heroísmo, served as learning centers for young women from wealthy families. There, women were educated in different subjects, including embroidery and lace making. The outcome was a combination of sacred and utilitarian art, which profoundly influenced the aesthetics of traditional embroidery.

The religious motifs found in the nuns’ work influenced the secular production of lace, with floral and geometric themes dominating the style. These practices continued outside the convent walls, with lace and embroidery being adapted for everyday use, but retaining the sophistication and detail they had been taught.

The Lace Evolution in Pico (19th and 20th Centuries)

During the 19th and 20th centuries, lace production in Pico went through a significant evolution. The introduction of new techniques, brought by immigration to the United States and Canada, resulted in an improvement in the quality of local lace. This period was marked by an increase in demand for handmade products, with lace being widely appreciated not only locally, but also on international markets.

In the 20th century, especially from the 1940s to the 1960s, the lace industry in Pico reached its peak. More than 500 women dedicated themselves exclusively to the production of lace, which became one of the island’s main exports. The lace makers worked in their houses or in small workshops, using simple tools but with extraordinary skills. The income earned from the sale of lace helped to support entire families, especially in times of economic and agricultural crisis.

The 20th century also brought the modernization challenge, with the introduction of sewing machines and the competition from industrialized products. However, Pico’s lace has continued to be valued for its authenticity and the handwork involved. Today, this craft tradition is preserved as part of the island’s cultural heritage, with ongoing efforts to bring the practice back to life and promote Pico lace as a symbol of identity and resilience.

Go to Types of Lace and Techniques >